— How do some languages get by without adjectives?

— What’s the difference between appositive and attributive phrases?

— What is reference, and how is it related to noun phrases?

Object denotation. The ability to precisely describe and point out a specific thing among many. You say a word — and I immediately know what you mean.

If there’s one thing that any human language must do really well — it’s this one. It’s the reason why most human languages have so many words: hard to be specific without a distinct piece of vocabulary per every kind of item, creature and phenomenon.

But no vocabulary can ever keep up with the real world. All languages might have a word for a tree — and even for different kinds of trees — but no language has a distinct word for each tree in the forest (newsflash: they’re all different trees). Many languages might have a word for a screwdriver — but no language has a word for a screwdriver of every possible tip size.

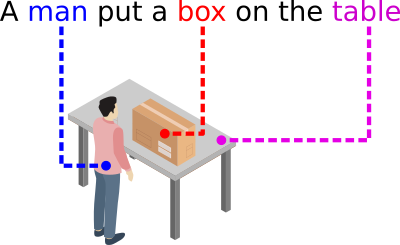

However, every language allows a way around this limitation: noun phrases. Sort-of “nouns“, but made of multiple words. Whenever you need to call something that doesn’t have a dedicated word for it — like my rusty black car across the street — you just take the word “car”, put the words “black” and “rusty” in front of it, and end up with something that points out that specific car among others.

But what’s the magic behind it? Is it just a blind sum of individual words, or is there some principle behind it?

Well, turns out that there isn’t one, but two kinds of magic, and different world languages rely on either one or the other to build noun phrases.

The familiar way

The “European” way of handling noun phrases requires two distinct classes of words. The first class is called nouns: words that name and point to object. And the second class are adjectives — those are special words that arguably don’t mean anything on their own, but can modify nouns.

A noun phrase must be initiated by a noun which “introduces” an object. Then, it can be further elaborated by adjectives. While “a box” means, essentially, a colourless box, “a red box” is a more descriptive expression that means a red-painted box specifically.

If nouns are pictures (which they sort-of are), then adjectives are overlay filters: words for colours work like colour filters, while adjectives for size and shape work like lens that magnify or distort the image.

Another name for such noun phrases is attributive phrases, because adjectives specify the attributes of the objects introduced by nouns.

However, the above representation of attributive phrases is not entirely accurate, for the following reasons:

- A box cannot really be colourless — it has to be of some colour.

- Nothing’s really stopping us from calling a red box just “a box”.

Apparently, the real difference between “a box” and “a red box” is that the former can refer to a box of any colour including red, while “a red box” can refer to red-coloured boxes only. Every red box can be calles “a box”, but not every box can be called “a red box”.

Thus, a noun doesn’t inherently mean a specific object: instead, a noun has a potential to mean infinitely many objects. I say “a tree”, and it can be any tree in the forest — and you never know which unless I elaborate.

This is what makes languages so powerful: we don’t need a separate word for every tree in the world, because the word “tree” covers them all. A noun is not a picture — but a set of pictures that includes every object that it could possibly mean:

© Auraiwan Dechsom

But what do adjectives do then? The answer: adjectives act as clip overlays that obscure and exclude some parts of a set. “A box” can mean boxes of any colour, but as soon as you add “red” to it, all non-red potential interpretations become impossible. Consecutive use of several adjectives over the same noun gradually triangulates the intended meaning.

Adjectives don’t paint or zoom onto nouns, but narrow them down.

The exotic way

Imagine a language with no adjectives at all: words for colours and qualities are there, but all of them are nouns.

- Instead of an adjective for “huge” — there’s a noun for “a hulk”

- Instead of an adjective for “old” — there’s a noun for “an oldster”

- Instead of an adjective for “wise” — there’s a noun for “a sage”

- Instead of an adjective for “green” — there’s a noun for “a green one”

- …

To make a noun phrase in such a language, you’d probably expect the speakers to just stack several nouns next to each other: to say “a hulk a man” instead of “a huge man”, or something. And you’d be correct.

Which doesn’t sound like a big deal: same noun phrases, words used to narrow down the meaning of other words — except apparently, any noun can modify another noun.

Right?

Not really. Under the hood, such noun series are nothing like the familiar noun phrases!

Take the noun “house”. As you already know, it can potentially mean any house in the world. However, in a real conversation, when you say “a house”, you usually have a specific house in mind: it may be your own house, or a house you’ve recently seen in a movie.

The properties of that house are immutable and don’t depend on the qty of adjectives: you had it in mind before you even started speaking. Whether you call it “a house”, “a red house”, “a small red house”, “a dark-brown-roofed red house” or even just “it” — it’s still the same little red house with a dark-brown roof and two facade windows. The only difference is how much information about the house you’ve chosen to give.

Truth is: whenever you narrow down a noun, you aren’t doing it for yourself, because you already know exactly what you’re talking about. Narrowing-down is always done for the listener.

To sum up, a noun has a set of possible meanings, which is part of its definition, its intrinsic property. However, the moment you actually use it in a conversation, it starts acting as a pointer and becomes tied to a specific thing.

This is called reference: the entanglement of a noun with a specific real-world object.

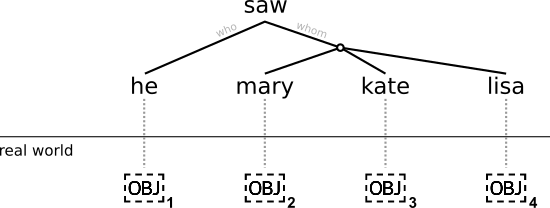

All noun phrases in a clause have to point at something — and generally, each of them points to its own thing. In the sentence “He saw Mary, Kate, Lisa”, the three names are a list of three different people. As a speaker of English, you wouldn’t interpret it as the first, middle and pen names of the same person: each of the names points to a separate woman.

Q: What’s it have to do with noun phrases?

Take a look at some descriptive words in Mudburra:

- dija — “a big one”

- kiyikarrangarna — “a red one”

- marduju — “a round one”

Each of the three is a proper noun and introduces its own set of possible meanings: the word “marduju” can mean all possible circular objects of any size or colour; “kiyikarrangarna” can mean any red-coloured thing; and “dija” can mean any big object in the world. Each can function on its own and point to a real-world object:

English: The big one stepped on something red while looking at something round.

Mudburra: Dija-li jamburlk lamarna kiyikarrangarna nyangani-ngka marduju-ngka.

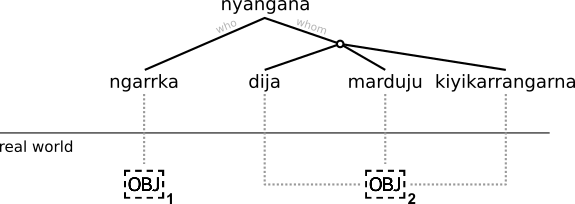

Now let’s see Mudburra handling noun elaboration:

English: a big red cirlce

Mudburra: dija marduju kiyikarrangarna (“big one” + “round one” + “red one”)

Basically, it’s a sequence of nouns. It’s a list, not-so different from “Mary, Kate, Lisa” mentioned earlier.

And that’s exactly how some languages narrow down onto objects: with a list! You simply put several plain, unmodified nouns — but have them point at the same object! As the “Mary, Kate, Lisa” example illustrates, English generally doesn’t allow it: a list of nouns has to be a list of different objects. But there is no inherenent reason why it has to be that way in every language, and quite a few languages allow coreferential list interpretations.

Hence, Mudburra phrase “dija marduju kiyikarrangarna” litterally means something like “A big thing that also happens to be a round thing and a red thing”. The same object has three identities at the same time.

The structure of the Mudburra sentence for “A man saw a big red circle”. Notice that reference aside, the structure is identical to the English enumeration example.

Such series of coreferential nouns is called an appositional construction. Strictrly speaking, an appositional construction isn’t even a true noun phrase, but a list of separate nouns that aren’t structurally connected in any way — but share the same reference.

Where true noun phrases rely on modifier words to clip a single set of potential meanings, an appositional construction has to rely on a different narrowing-down principle. Because not only there are no modifier words, but multiple nouns all pointing to the same object essentially means multiple sets of potential meanings. A circle, a big thing, a red thing — the same object must be all of those things at the same time for the appositional construction to make sense.

Simply put, the same object must be present on all three sets.

Thus, the meaning of the entire construction is triangulated via intersection of multiple sets rather than clipping: the potential meanings shared by all participating sets is the net meaning of the entire construction.

Q: Still, what’s the big deal? What’s stopping us from claiming that the English “big red circle” works the same: the intersection of all potential circles × all potential red things × all potential big things?

Here are are some non-trivial differences:

(1) In true noun phrases, there is a clear distinction between the head and the modifier(s) of a phrase. In English “big circle”, only one of the words is the identity of the object (“what is it?” — “it is a circle”; but not “it’s a red”).

Meanwhile, there is no such distinction in appositional constructions — it’s impossible to tell the head from the modifiers. Mudburra “dija marduju” could equally stand for a round thing that happens to be big, or a big thing that happens to be round. The object is both things at the same time: it has two identities, with neither being dependent on the other. Either word would be a perfectly valid answer to the “what is it?” question.

(2) Being structurally a list of nouns makes apposition indistinguishable from enumeration of multiple objects — as both look identical. For example, “marluka warnayaka” could equally mean “an old stranger” or “an old man and a stranger”. Without contextual clues, it’s impossible to tell if the noun sequence is a list of two objects or two identities of the same object.

The not-so exotic way

Apposition may be a go-to way of narrowing down in some languages. However, it turns out that apposition can be found even in languages that generally rely on attribution — including English:

My brother Nathan is here.

Alex the genius wrote it.

The dessert, the chocolate cake, was delicious.

Our teacher, the Frenchman, entered the classroom.

The above examples illustrate how an object can be elaborated in English by having two syntactically distinct noun phrases point to the same referent.

- An appositional construction is essentially the same object referred twice by two separate noun phrases. The object litterally has two identities at the same time: it’s both my brother and Nathan, or both Alex and a genius.

- Neither noun phrase is dependent on the other: either could work alone and the sentence would still be valid. It’s impossible to tell which of the two modifies the other.

- Structurally, the two phrases just go one after another as a list without any formal relationship markers.

This phenomenon, uncommon in English, gives us a glimpse into how the nouns are narrowed down in apposition-heavy languages.